The Passing of Dr. Gerald Whitehead Deas

By Office of the President | Jan 23, 2026

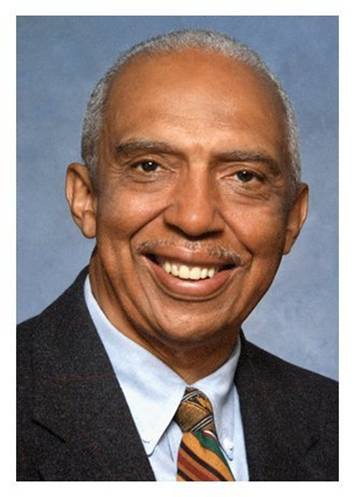

SUNY Downstate mourns the passing of Gerald Whitehead Deas, M.D., MPH, MS, Hon. Sc.D., Hon. D.H.L. He was a singular presence in this institution’s life and an original in every sense.

SUNY Downstate mourns the passing of Gerald Whitehead Deas, M.D., MPH, MS, Hon. Sc.D., Hon. D.H.L. He was a singular presence in this institution’s life and an original in every sense.

Dr. Deas, also known affectionately as Jerry, was a proud 1962 graduate of SUNY Downstate’s College of Medicine. He carried Downstate with him wherever his work took him. He believed that medicine and public health extended beyond exam rooms and lecture halls and belonged in everyday conversations at kitchen tables, on stoops, on subway platforms, and in quiet moments of daily life.

Born and raised in Brooklyn, Dr. Deas attended Boys High School and Brooklyn College, where he earned bachelor’s and master’s degrees in biochemistry. A Korean War vet, Dr. Deas continued his education at the University of Michigan, where he received a master’s in public health. He enrolled at SUNY Downstate, where he earned his MD degree in 1962 and was one of only three African American students in his graduating class. Dr. Deas subsequently completed an internship and residency training at Kings County Hospital, and later served as an attending physician at Jamaica Hospital and Mary Immaculate Hospital in Queens.

Dr. Deas loved the quick turn of a phrase, a shared moment of humor, and the way a sentence, done right, could make difficult information feel manageable. One of his favorite reminders began with his own name: DEAS = IDEAS, a concept he turned into a baseball cap that he freely distributed as his calling card and a gentle reminder to keep thinking, learning, and caring.

Dr. Deas served as Director of Health Education Communications and Assistant Professor of Preventive Medicine, retiring in 2018. In 2019, Downstate awarded him an Honorary Doctor of Science, recognizing the reach of a career built on service, creativity, and conviction.

His influence extended far beyond our campus. He became the first Black medical columnist for the New York Daily News, wrote over 1,000 articles for the New York Amsterdam News, and used radio and television to translate health information into guidance people used daily. Specific chapters of that work lay especially close to his heart.

In the 1970s, Dr. Deas led a public health campaign involving the Argo Starch Company that went beyond a dispute with a corporation. It was an act of protection and a call to elevate community voices to reduce harm and improve health outcomes.

In his clinical practice, he noticed that many Black women consumed an unusual snack—cubes of laundry starch. Some believed the practice stemmed from traditions of clay consumption in parts of Africa. Dr. Deas quickly determined that ingesting starch interfered with iron absorption and frequently caused anemia. Today, Argo Starch clearly states that its product is not intended to be eaten raw. He remained proud of its lasting impact, including the special commendation he received from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration.

He also helped found Doctors Against Murder, a name marked by wordplay, yet grounded in purpose. Dr. Deas maintained that violence was a public health issue that demanded attention.

He believed in friendship and collaboration. Few relationships mattered more to him than his bond with his Queens neighbor and friend, Bill McCreary, the legendary broadcaster behind the Emmy-winning McCreary Report. For ten years, Dr. Deas was the program’s chief medical correspondent, united by a shared belief that media can and should serve the public good.

Equally important was his long-standing relationship with the Arthur Ashe Institute for Urban Health, a partnership rooted in shared values and shared ground, and in the conviction that health equity required presence, persistence, and plainspoken truth. It mattered deeply to him to stand alongside an institution that approaches urban health as a daily responsibility. When the Arthur Ashe Institute honored him with its Legacy in Motion Award, it recognized a man who spent a lifetime translating concern into action and drawing people into the work.

Over the years, Dr. Deas received many honors, but accolades were not how he measured success. His greatest legacy is the number of students, especially those from minority and disadvantaged backgrounds, who found their way into medicine because he made time, made space, and made them feel seen. He spoke in churches and schools, encouraged young people to expand their lives through education, and here at Downstate, his door remained open to anyone, particularly students, who needed help, guidance, or a friendly word.

We extend our deepest condolences to Dr. Deas’s wife of 67 years, Beverly, their three children, loved ones, former students, colleagues, and the many communities he served. We will forever remember his wit, generosity, and steady insistence that ideas can change health and change lives. He will be deeply missed by many who continue to carry his legacy forward.