Profile: About Dr. Deas

While some people wear a monogram to let us know who they are, Dr. Gerald Whitehead

Deas adds an extra letter to his name. What we see is IDEAS. This is his way of enjoining

us to think logically and put our best ideas into action.

While some people wear a monogram to let us know who they are, Dr. Gerald Whitehead

Deas adds an extra letter to his name. What we see is IDEAS. This is his way of enjoining

us to think logically and put our best ideas into action.

He Does It His Way

Physician, poet, patient advocate, playwright, media personality, political activist, public health crusader - Gerald W. Deas, M.D., MPH, MA, is all of these, and more. He has battled major companies and organized whole communities to protect the public's health.

Born and raised in Brooklyn, Dr. Deas attended Boys High School and later Brooklyn College, earning a bachelor's and a master's degree in biochemistry. Drafted into the Army during the Korean War, he helped to identify the remains of fallen comrades. Out of this gruesome experience, he developed a lifelong hatred of war and its aftermath. Years later, after witnessing how violence in our neighborhoods was claiming the lives of so many youths, Dr. Deas and other physicians at Downstate and Kings County Hospital Center organized Doctors Against Murder (DAM) to encourage young people to reject violence.

Home from the war, Dr. Deas resumed his education with a single-minded purpose: to become a healer. After receiving a master's in public health from the University of Michigan, he enrolled at SUNY Downstate and became an M.D. in 1962.

In those years, few African-Americans enrolled in medical school, but Dr. Deas's talents were soon evident to the faculty as well as to his fellow students, who elected him class president.

After graduation, he performed both his internship and residency training in internal medicine at Kings County Hospital. In addition to joining the faculty of preventive medicine at Downstate, he served as an attending physician at Jamaica Hospital and at Mary Immaculate Hospital in Queens for 35 years.

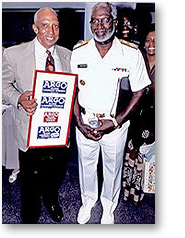

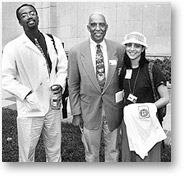

U.S. Surgeon General David Satcher congratulates Dr. Deas for his role in making the Argo Starch Company place a warning label on its laundry products stating "Not Recommended for Food Use."

Dr. Deas is adept at networking and using the media to foster public health awareness. His successful struggle in the 1970s against Argo Starch Company is legendary. After discovering that laundry starch was being sold in grocery aisles as a snack, causing black women to become anemic, Dr. Deas forced Argo to repackage its product in powdered form and to add a warning label, "Not Recommended for Food Use." In recognition of this service, the Food and Drug Administration awarded him a special commendation.

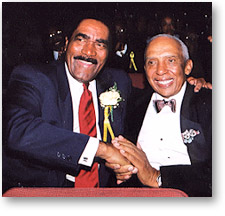

Emmy-award winning journalist Bill McCreary and Dr. Deas have been friends since the time they worked together on television's McCreary Report.

The first black medical columnist for the New York Daily News, Dr. Deas was medical correspondent for television's McCreary Report for 10 years, hosting the segment called "House Calls." He also hosted a weekly radio show on WLIB. He continues to write regularly for the Amsterdam News and other local papers.

As director of health education communication at Downstate and host of "Health Center," the cable TV show produced on campus, Dr. Deas alerts the public about such health hazards as food dyes and additives in sugary drinks that can trigger asthma attacks and behavioral problems in children.

At the 2002 Sports Ball, sponsored by the Arthur Ashe Institute for Urban Health, Dr. Gerald Deas, shown with fellow honoree Russell Simmons, received the Legacy in Motion Award for his leadership in urban medicine.

Dr. Deas also uses the transforming power of poetry and music to convey his message. Pulitzer-Prize winning poet Gwendolyn Brooks has praised his poems as "rich with creative excitement." Often they contain warnings about common health dangers (Mr. Mean Nicotine and Sodium Confesses), or reminders for patients to take their medications (Cautionary Tale of Hattie Brown). His lament about a child suffering from sickle cell disease (A Black Child Who Can't Smile) was at one time a March of Dimes theme song. He also has written numerous musicals and plays that continue to be performed Off-Broadway.

To his students, Dr. Deas exemplifies both compassion and strength in the fight to protect public health.

Much more could be said about this "old-fashioned country doctor," as he has been described by the New York Times, who has worked so hard to spread public awareness about sarcoidosis and other hidden diseases, and was making house calls until the age of 70. Although he has received a great many honorifics and awards, he prefers not to frame them but to give them away to young people. "They're the ones who need the encouragement," he says.

Dr. Deas credits his wife, Beverly, to whom he has been happily married for more that 45 years, for helping him through thick and thin.

She supported him during eight years of medical training, managed his private practice, often accompanied him on late night house calls, typed and edited his work for the media - and accomplished all this while also raising three children.