Redefining AAPI Leadership in Medicine, Academia, and Health Equity

By Office of the President | Jun 3, 2025

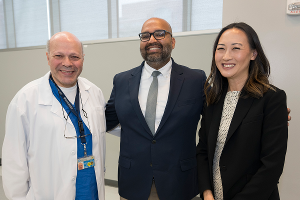

Left to Right: Dr. Bob Wong; Ms. Tina Kim, Dr. Jennifer Park, Dr. Ranjita Raghavan, Dr. Vikram Pagpatan, on screen is Dr. Subodh Saggi

Asian American and Pacific Islander (AAPI) communities’ contributions are vital to the U.S. healthcare system as clinicians, researchers, educators, public health leaders, caregivers, advocates, innovators, community organizers, and essential members of the healthcare workforce. Their contributions span direct care, scientific advancement, system improvement, and culturally responsive community engagement. Yet, numerical presence alone does not equate to equity. AAPI professionals remain underrepresented in executive leadership, policymaking, and academic governance. Cultural misrecognition, implicit bias, and structural norms continue to shape their experiences and constrain advancement.

“AAPI” encompasses various ethnicities, languages, migration histories, and cultural identities, from Southeast Asian refugees to Pacific Islander educators and South Asian physicians. Institutions often overlook this internal diversity. Research rarely reflects these distinctions, and leadership development models usually fail to align with the cultural values present in many AAPI communities.

Efforts to advance equity must closely examine the barriers facing AAPI professionals. Biases, subtle and overt, persist even within organizations committed to diversity. Addressing these challenges requires more than representation; it demands institutional reform, culturally grounded mentorship, and inclusive leadership models.

Downstate’s 2025 AAPI Heritage Month panel, Not Just a Demographic: Shaping Health Equity from Within, convened leaders in medicine, academia, public health, and policy to explore these issues and offer solutions rooted in cultural relevance, institutional accountability, and equity-driven practice.

Jennifer Park, M.D., Assistant Professor of Ophthalmology and Director of the Cornea Service, shared a revealing moment. She described entering an exam room to treat a returning patient and introducing herself again. As the examination progressed, the patient asked when the surgeon would arrive. For Dr. Park, such encounters are every day. Despite qualifications and departmental leadership, she remains subject to dismissal and doubt, an experience familiar to many AAPI medical professionals.

Dr. Park’s account illustrates how bias persists in environments that consider themselves inclusive. Her repeated experiences of misidentification reflect institutional blind spots rather than isolated misunderstandings.

The panel examined cultural and structural barriers that limit AAPI advancement. Moderator Vikram Pagpatan, Ed.D., OTRL, Associate Professor of Occupational Therapy and former president of the Asian-American Pacific Islander Occupational Therapy Association, encouraged attendees to assess AAPI representation beyond headcounts. AAPI professionals do not fulfill quotas; they drive innovation, shape policy, and influence health systems, and their absence from leadership affects patients, communities, and institutional progress.

Cultural context further complicates clinical care. Ranjita Raghavan, M.D., Clinical Assistant Professor of Emergency Medicine, explained how cultural norms shape symptom reporting. Some patients underreport to avoid burdening providers. Others exaggerate symptoms after learning subtlety leads to dismissal. In emergency settings, these mismatches can delay diagnosis and impair outcomes.

Robert K.S. Wong, Ph.D., Distinguished Professor and Chair of Physiology and Pharmacology, asked a foundational question: What if prevailing leadership models exclude rather than elevate? He noted that academic medicine often defines leadership by assertiveness and self-promotion, which conflict with cultural values rooted in humility, collaboration, and group harmony. Institutions that reward only visible assertiveness may overlook professionals who lead through shared responsibility and team-based influence. Dr. Wong called for broader frameworks that reflect diverse leadership styles.

He also rejected viewing AAPI communities as a single entity. While aggregate data may suggest low suicide rates among Asian Americans, disaggregated data reveals disparities. Vietnamese American youth experience suicide at a rate of 10.57 per 100,000; Indian American youth show the lowest rate at 6.91 per 100,000. Critical differences remain hidden without subgroup data, and policies miss those in greatest need. For Dr. Wong, recognizing these distinctions is a scientific and moral necessity.

Subodh J. Saggi, M.D., MPH, Professor of Medicine and Program Director of Nephrology, extended this analysis to chronic disease. His work with Afro-Caribbean and South Asian populations shows how biological risk intersects with structural barriers, limited access to culturally tailored nutrition counseling, language discordance, and financial constraints. These factors influence diagnosis, adherence, and care outcomes. For Dr. Saggi, disaggregated research is both evidence-based practice and advocacy. It challenges institutional neglect and brings visibility to overlooked populations.

Tina Kim, MSPH, Deputy Commissioner for the New York State Department of Health’s Office of Health Equity and Human Rights, described how her office integrates equity into state contracts and programs. Still, she warned that seemingly neutral policies, such as hiring criteria based on dominant communication styles or individual achievement, can exclude qualified candidates and reinforce structural bias.

Panelists addressed a central contradiction: AAPI professionals are overrepresented in training pipelines yet underrepresented in leadership. Their presence in medical schools and residencies contrasts their absence from deanships, department chairs, and policymaking roles. This disparity suggests that barriers to advancement differ from barriers to access.

The model minority stereotype intensifies these challenges. It presents success as a given yet pressures individuals to remain silent about exclusion. Institutional change requires more than visibility; it requires advocacy, solidarity, and accountability.

The panel affirmed Downstate’s commitment to inclusive leadership development. Advancing equity involves mentoring that honors cultural context, producing research that reflects community complexity, and designing leadership pathways that welcome multiple expressions of excellence.

The path forward requires recognizing AAPI diversity as an institutional strength. Disaggregated data must inform decision-making. Culturally responsive practices must guide care. Inclusive leadership models must reflect the broad range of voices, values, and visions that AAPI professionals bring to academic medicine.

Tags: Health Equity